Think Again...

THINK AGAIN

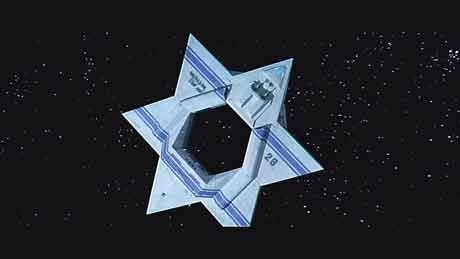

Think Again: Israel

Six decades after its founding, the Jewish state is neither as vulnerable as its supporters claim nor as callous and calculating as its critics imagine. But if it is to continue defying all expectations, Israel must first confront its own mythology.

BY GERSHOM GORENBERG | APRIL 10, 2008

"Israel Is a Successful Democracy"

Sort of. From what began as an impoverished and war-ravaged country flooded with Jewish refugees from Europe and the Arab world, Israel has grown into a regional military power with a per capita GDP that exceeds all its neighbors. Unusual among post-World War II states, it has also managed to maintain an uninterrupted parliamentary regime for 60 years. Israel's status as the Middle East's only credible democracy plays a major role in its close alliance with the United States and its generally warm relations with Europe.

But how well is that democracy working? Israel elects its leaders, and its vigorous free press sometimes publishes criticism that might be considered anti-Israel elsewhere. Much of that criticism is aimed at the undemocratic regime in the West Bank: Jewish settlers enjoy the full rights of Israeli citizens, while Palestinian self-rule is limited to enclaves.

Within Israel proper, democracy is functioning but fragile. The lack of a written constitution has left the creation of civil rights to an activist Supreme Court -- from a landmark 1953 decision that kept the government from closing newspapers, to last year's ruling that enshrines the right of same-sex couples to adopt children. But the court's position is tenuous. Some in Israel want the Knesset, Israel's parliament, to restrict its powers to overturn laws, rule on security matters, or accept human rights cases.

Another critical weakness is the status of the Arab minority, one fifth of the population. Officially, Arabs have equal rights. But they're scarce in the civil service. Arab towns and cities get less funding from the central government than Jewish municipalities. Roughly an eighth of the country's land is owned by the Jewish National Fund, whose policy of leasing land only to Jews is at the center of a long legal battle.

Arab parties, which hold only 10 out of the Knesset's 120 seats, have been consistently left out of government coalitions. Not only does that exclude Arabs from power but it also makes forming a majority coalition much more difficult -- a central, and rarely noticed, reason for the chronic instability of Israeli governments.

The crumbling of the major parties that once dominated Israeli politics has made coalition government a shaky proposition. Labor, Likud, and Kadima -- a centrist breakaway from the Likud -- now hold only 60 Knesset seats between them. Labor leader Ehud Barak and Likud chief Benjamin Netanyahu are both ex-prime ministers who lost their jobs in landslides, reflecting their parties' failure to attract new leadership and the public's disgust with politics. Solving the diplomatic impasse with the Palestinians -- the country's key challenge -- is made much more difficult as a result. Israeli democracy is alive, but it needs an infusion of new blood.

"Israel Is a Jewish State"

Not in the way that you think. In Western countries, "Jewish" is usually considered a religious category, parallel to "Catholic" or "Muslim." So "Jewish state" sounds akin to "Islamic republic."

But Zionism -- the political movement that created Israel -- was born of 19th-century nationalism, and it defined Jews as an ethnic group, a nationality like "Russian" or "French." Inspired by other contemporary nationalist movements, early Zionists transformed the traditional Jewish aspiration to return to the Land of Israel (a.k.a. Palestine) into a modern nationalistic program. Jews needed to revive their historical language, but religion was a relic of the past, an obsolete vehicle for maintaining ethnic identity in exile.

Israel's secular Jewish majority is heir to that conception. For Israel's secular elite, being a Jew means speaking Hebrew, living in the Jewish homeland, and belonging to Israeli society. Jewish holidays are national holidays -- to be spent hiking, at the beach, or overseas, not in a synagogue.

The theocratic side of the Israeli polity is largely a relic leftover from Ottoman law. Marriage and divorce are controlled by religious authorities, so Jews can only wed through the state-run rabbinate. Catholics must marry through the church, and they can't divorce at all.

Otherwise, the clergy has little power. Completely secularizing the state would not end the real divide in society, which is an ethnic split between Jews and Arabs. As a key example, universal military service is central to civic identity -- but Arabs are exempt. Arabs tend to regard themselves as Palestinian citizens of Israel, but not as "Israelis." Unless an overarching Israeli identity can be created and Arabs can be integrated into the mainstream, Arab demands for rights as a national minority will only grow.

"Israel Was Born of the Holocaust"

No. Israel was born despite the Holocaust. Every visiting foreign dignitary is taken to Yad Vashem, the official Holocaust memorial. The route proceeds from exhibits on the horrors of the death camps to the establishment of the Jewish state. The stress on the Holocaust reflects the emotional trauma that the horror still inflicts on Jews. It also underpins the political message that Jews can only be safe in their own state.

But an additional message is that Israel was created as a response to the genocide perpetrated against Jews in Europe. That's a historical mistake, and promoting it is politically costly for Israel. As an organized political movement, Zionism began in 1897, decades before the Nazis took power in Germany. Modern Jewish migration to Palestine began even earlier, not just from Europe but also from Yemen, Central Asia, and other parts of the Muslim world. Early Zionists did see anti-Semitism as proof that in an age of nation-states, Jews needed one of their own. But they built their plans on Europe's Jews moving to Palestine. Those numbers would ensure that Jews would grow from a small minority to an overwhelming majority in the country.

In 1939, there were 8.3 million Jews in the territory that would come under Axis rule. Six million were murdered. The Holocaust orphaned the Jewish independence movement, whose largest source of support and immigrants was wiped out. The state that was established was much weaker than it would have been.

When Israel bases its public relations on the Holocaust, it unintentionally lends support to the Arab argument that Palestinians are paying for Europe's sins, a talking point intended to undercut Israel's legitimacy as a Jewish home and shift Western support to the Palestinians.

There's one sense, though, in which the Holocaust formed Israel: Psychologically, it created the feeling that Jews stand in constant threat of annihilation.

"Israel's Existence Is in Danger"

Not anymore. When Israel declared independence on May 14, 1948, its Arab neighbors responded by invading. "It does not matter how many [Jews] there are," said Arab League Secretary-General Abdul Rahman Azzam. "We will sweep them into the sea."

Instead, disorganized and inexperienced Arab armies quickly crumbled before them. By the war's end, Israel held more land than the United Nations had allocated it. Before the June 1967 Six Day War, as Arab states massed their forces on Israel's borders, Israelis feared a second Holocaust. Israel's astonishing victory showed that it had become the regional superpower, a status confirmed when it repulsed Egypt and Syria's surprise attack in October 1973. Five-and-a-half years later, the peace agreement with Egyptian President Anwar Sadat neutralized Israel's most formidable foe.

Today, there is no conventional military threat that remotely compares with the alliance led by Egypt. Left isolated by the Israeli-Egyptian peace, Syria has carefully observed a cease-fire since 1974. Afraid to risk full confrontation, Damascus has supported substate forces such as Hezbollah in Lebanon and Hamas in the Palestinian territories. Along with other guerrilla groups, they employ terrorist tactics and rocket fire. Those methods have claimed many Israeli civilians' lives. But on a national level, they're equivalent to a chronic illness, not a fatal disease.

"A Nuclear War Would Destroy Israel"

No. If conventional armies don’t endanger Israel's very existence, then what of an Iranian bomb? Benjamin Netanyahu, now leader of Israel's right-wing opposition, said in a typical speech, "It's 1938, and Iran is Germany." Prime Minister Ehud Olmert has made similar comments. The 2007 U.S. National Intelligence Estimate's assertion that Iran has stopped its nuclear weapons program has done little to reassure Israeli leaders or citizens.

Although all nuclear proliferation is dangerous, the rhetoric ignores the regional power balance. Israel does not normally say it has nuclear arms. But Olmert slipped in 2006, classifying Israel as a nuclear power. Foreign reports sometimes refer to Israel's presumed second-strike capability, the ability to destroy an enemy even if the enemy were to strike first. Such deterrence kept the Soviet Union and the United States from using nuclear weapons during the Cold War.

A common argument is that deterrence won't work as it did with the Soviets. Iran's fundamentalist leaders would supposedly be willing to commit national suicide to fulfill their irrational ideology. Experience shows, however, that Iranian leaders share the Soviets' caution. Iran agreed to a cease-fire in the war with Iraq once Iraqi missiles began falling on Tehran. The ayatollahs were willing to sacrifice soldiers -- but not to pay a higher price. The threat of mushroom clouds will concentrate their thinking about Israel wonderfully.

It's true that Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad's extreme anti-Israel rhetoric and Holocaust denials are perfectly pitched to frighten Jews. But when Mohammad Khatami was president of Iran, we were told that his moderation made little difference because real power lay with the ayatollahs. For the same reason, one should avoid overestimating Ahmadinejad's clout.

Iran's underlying reason for wanting nukes is nationalist and fairly pragmatic: It seeks to assert its role as a regional power and to deter other nuclear powers. The real risk is that it will set off a regional race for the bomb. The more fingers there are on more buttons, the greater the chance of a mistake. Complacency would be a mistake -- but so is panic.

"Hamas Seeks Israel's Destruction"

In its dreams. Hamas's founding charter, issued in 1988, defines Palestine as "an Islamic waqf" -- sacred trust -- "consecrated for future Muslim generations." That includes pre-1967 Israel. All of Palestine, says the charter, must be liberated by jihad. Diplomacy is a "vain endeavor." The document turns the goals of radical Palestinian nationalism into timeless religious truths.

Yet with time, Hamas has indeed changed. It hasn't renounced its charter, but has stopped referring to it. The movement has gradually morphed into a hard-line but more pragmatic Islamist organization. A milestone was its decision to participate in Palestinian Authority elections, even though the Authority was born of the Oslo agreements with Israel. In its 2006 election platform, Hamas stressed liberating the land that Israel occupied in 1967, even while insisting that it would not renounce the claim to pre-1948 Israel or Palestinians' right of return.

This balancing act looks much like the change that the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) underwent a generation ago, when it adopted its 1974 "phased strategy" -- willingness to establish a state in part of Palestine while maintaining a claim to the rest. For the PLO, that was a way to justify participating in diplomacy on the future of the occupied territories, and it was a step toward recognizing Israel. Today, there are disagreements within Hamas over whether to negotiate directly with Israel. However, the organization appears willing to accept a de facto two-state solution and long-term cease-fire, as long as it doesn’t have to recognize Israel outright.

Not that Hamas has turned moderate. It hasn't renounced "armed struggle," including attacks on civilians. It may be willing to put up with Israel's existence, but it still hasn’t negotiated with itself the way to say so publicly. Nonetheless, an eventual agreement with Israel is within the realm of the possible.

"The Israel Lobby Controls U.S. Policy"

Never. In their book The Israel Lobby and U.S. Foreign Policy, John J. Mearsheimer and Stephen M. Walt hold the lobby largely responsible for U.S. policy not only toward Israel but toward the rest of the Middle East. The book's greatest flaw may be that it serves as an unintended advertisement for the central lobbying group, the American Israel Public Affairs Committee (AIPAC), which is eager to play up its own influence.

Although AIPAC does lobby the U.S. Congress effectively, its influence on policy has limits. Under former President Ronald Reagan, it lost its fight to prevent the sale of AWACS surveillance planes to Saudi Arabia. It could not prevent Bush Sr. from using loan guarantees as a means of pressuring Israel on West Bank settlement. Under Bill Clinton, AIPAC helped push through legislation aimed at moving the U.S. Embassy from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem, despite the potential for upsetting peace talks. But the victory was hollow: As passed, the law contained a presidential waiver that Clinton and George W. Bush have repeatedly invoked to avoid the move. In 2006, despite AIPAC’s efforts to pass a version of the Palestinian Anti-Terrorism Act that would have virtually cut off U.S.-Palestinian relations, the U.S. Congress opted for a more moderate bill.

Attributing U.S. policy solely to AIPAC has the advantage of great simplicity. That is also precisely what's wrong with it. The constraints on U.S. policy in the Middle East were laid out after the Six Day War, in a memo to then President Lyndon Johnson written by McGeorge Bundy, his former national security advisor. The United States is committed to Israel's survival, Bundy wrote, but also to good relations with pro-Western Arab states that want Washington to tilt against Israel. Keeping Israel strong saves the United States the headache of defending it directly. But in the long run, Bundy implied, getting Arabs and Israelis to make peace was the only way to resolve the contradictions in U.S. policy. American administrations have oscillated between these conflicting concerns ever since.

At 60, Israel is neither a perfect democracy, nor a Jewish ghetto imperiled by Iranian Nazis, nor a puppet master indirectly controlling Washington. It is more democratic than its neighbors, more reliably pro-Western, and more successful economically and militarily. Nonetheless, it faces the classic dilemmas of a nation-state dealing with minorities, borders, and neighbors. In other words, it is best understood as a real place, not a country of myth.

so you could see it's even-handedness. However, the highlighted portion is the direct response to your claim.

You're wrong. And there's facts to show it. Surprise, surprise.